Infection Resilient Environments: Time for a Major Upgrade

BlogWritten by

Shema Bhujel, Policy Officer, Royal Academy of Engineering

“The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the risks of airborne disease and the importance of well-maintained indoor environments, with good ventilation and indoor air quality.“

In the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Government Chief Scientific Adviser Sir Patrick Vallance invited the National Engineering Policy Centre (NEPC), to identify the interventions needed to reduce transmission of infections in the UK’s built environment and transport systems.

We explored this commission in a two-phase programme of work. The first phase looked at near-term improvements ahead of winter 2021/22 and uncovered systemic flaws in the way we design, operate and manage buildings for infection control. The second phase asks why these vulnerabilities exist at all and what needs to change in order for the UK building stock to be better placed to reduce transmission in future pandemics as well as protect people from seasonal disease outbreaks.

Published in June, ‘Infection resilient environments: Time for a major upgrade’ reflects on how the design of public spaces, building and transport systems affect public health. Throughout history, pandemics and epidemics have changed urban planning to improve public health outcomes. A notable example is the cholera epidemics of the 19th Century in Europe which led to the development of the modern sewage and sanitation systems and the right to clean potable water. Similarly, the COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the risks of airborne disease and the importance of well-maintained indoor environments, with good ventilation and indoor air quality. When elimination of a disease is not achievable, engineering controls in the built environment can play a critical role in reducing the risks of infection transmission. Embedding these measures in our indoor environments creates an opportunity for longer-term improvements to develop infection resilience, creating safer, healthier and more sustainable environments for those who use them.

In monetary terms, a commissioned economic analysis found that, in the event of another severe pandemic in the next 60-year period, the estimated societal cost of infection caused by influenza-type pandemics and seasonal influenza in the UK could amount to £23 billion a year. Even outside of the extreme circumstances of a pandemic, the lives lost and sick days caused by seasonal influenza amount to an estimated annual cost of £8 billion, costs which are not evenly distributed across the population or the building and transport stock. Everyone has a right to expect that buildings and transport provide infection resilience, therefore action is required to reduce the risk of transmission as well as the associated costs.

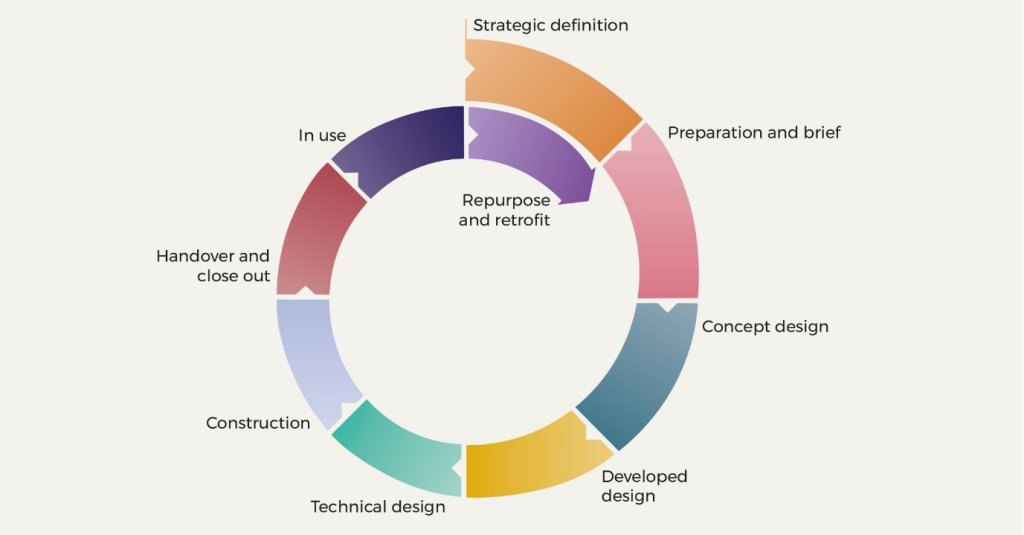

Figure 1. Stages of a building lifecycle

We gathered evidence on the limitations of the current system looking across all the stages of the building and transport lifecycle from strategy and design, construction, and handover, to in-use and retrofit (Figure 1). This involved consideration of how to embed infection resilience in both existing and future building stock and public transport. To identify the right changes, the implications of the recommendations were also considered through five lenses of resilience: health, economic, social, environmental and governance systems to ensure alignment with broader societal goals.

We found that for the initial stages, strategy and design should be driven by a people-centric approach that understands end-user needs, and designs for improved health and wellbeing of users. To develop a clear baseline of what best practice in infection resilience looks like, there is a need to develop meaningful standards that can be embedded into existing design and operational practices.

As split incentives in the sector often mean that benefits are not accrued by the stakeholder bearing the cost, meaningful changes in practice will rely on substantial directives from regulation. For design and construction, considerations of health should have greater prominence within building regulations to support a culture shift towards valuing the role of the built environment for health and wellbeing, alongside other requirements such as structural and fire safety.

The commissioning process where buildings are tested to ensure effective operation sometimes fails to ensure that the building is functioning as designed. The process is often time-limited, under-resourced and the regulatory requirement is poorly enforced. There is a need to drive improvements to the commissioning and testing of the building systems.

After the building is handed over, building regulations no longer apply. This creates a performance gap as systems break down or are no longer operated as they were designed. To maintain standards of safe and healthy building performance over a building’s lifetime, in-use regulations need to be established so responsibilities of building owners and managers for the maintenance and use of systems can be clearly understood and enacted.

Where improvements cannot be made to the building fabric or in public transport, other technical solutions can play an important role to reduce infection transmission such as air cleaning devices, which may be useful in buildings with poor ventilation. However, there is a lack of effective mechanisms to verify the claims of manufacturers and to understand the operational efficacy of these products. To enable innovation, assure the efficacy of technical products and systems, and provide guidance for those adopting them, standards are needed.

Given our built environment needs to be resilient to a wide range of future risks, infection resilience should be aligned with net zero goals. To seize the opportunity created by the net zero strategy, major retrofit programmes should also address infection resilience, to deliver safe, healthy, and sustainable infrastructure.

There is a lack of public awareness of the effects of indoor environments on our health. There is a need for a public campaign to ‘make the invisible, visible’. In particular there is a need to target building and transport owners and management, who have responsibility for creating good environments for work and leisure, and for delivering that healthy indoor environment that everyone has the right to assume.

Developing infection resilience requires considering the interactions between health, economic, governance, environmental and social factors. For such changes to work effectively, strategic coordination is needed across government departments to deliver joined up policy making.

In response to these challenges, ‘Time for a major upgrade’ presents eight recommendations that together outline the coordinated actions needed to embed infection resilience. To be successful, all of these changes must be informed by multidisciplinary research. There is a clear need to maintain and grow the collaborative research networks across public sector research laboratories, government departments, industry and academia, that have been developed over the COVID-19 pandemic.